Demystifying the Border Crisis

Aug. 28, 2024

It was not that long ago that immigration was a relatively less partisan issue in the US. This is not to say it was not controversial; both immigration, and anti-immigration backlashes have shaped US politics since its founding. But it was not always an issue that so easily fell along party lines. Both major parties of the modern era had split factions: the Republicans had both a nativist wing and a business wing that sought new low wage workers; the Democrats had both naturalized “ethnic” voters and labor unions which saw new immigrants as competitors. Today, Democrats are largely seen as pro-immigration and Republicans as anti. However, as late as the George W. Bush presidency, the Republican Party made credible efforts towards immigration reform, and the last president to grant large scale amnesty to immigrants without legal status was Ronald Reagan.

The flashpoint of today’s immigration debates is the southern border of the US. But immigration is not only – or even mostly – a border phenomenon. Below are some myths and realities about immigration.

Myth: Most unauthorized migrants crossed the border

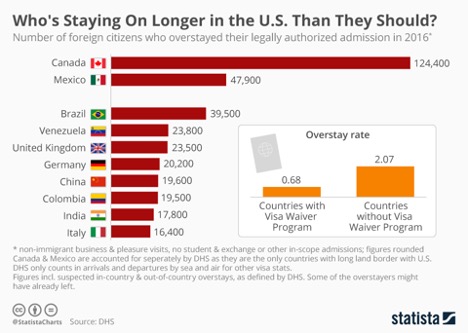

Most people who are in the US without authorization – i.e. illegal or undocumented immigrants – did not arrive in the country illegally. Most, in fact, did not cross the southern border at all. Twice as many came legally, on visas, and simply overstayed. Many of those flew in to airports rather than crossed over land, but in either case, they did not sneak in. Once one has overstayed one’s visa, one is officially out of status – that is, “illegal,” and subject to removal – that is, deportable. Yet most are not arrested and put into removal proceedings. This is because the US prioritizes criminal deportations: removing those who have committed some kind of crime, after they have gone through the criminal justice system here. And unlawful presence in the US alone is not a crime. Improper entry – that is, crossing the border without authorization, is a crime, however it is a misdemeanor, punishable by no more than 6 months in jail and a $250 fine. Anyone who has driven under the influence has committed a more serious crime – and more “illegal” – than someone who crossed without authorization.

Yet we don’t hear about the vast majority of undocumented immigrants in the US: that is, visa overstayers. One reason is they do not fit the profile of what we imagine undocumented immigrants to look like. The top country of origin for visa overstayers is Canada. Yet there are few people calling for the mass deportations of all the illegal Canadians in the US.

Source: Buchholz, Katharina. “Visa Overstays Outnumber Illegal Border Crossings.” Statista Jan. 18, 2019.

Myth: Asylum seekers are breaking the law

Rather than visa overstayers, most of the coverage of immigration has focused on one particular group of would-be migrants, asylum seekers. Yet unlike visa overstayers, who are unauthorized, asylum seekers are following the law. Asylum is a legal process, under both US and international law. It traces back to the Holocaust, and the shame that the world felt for having turned away Jews and other victims of the Nazi regime rather than provide them refuge. Following World War II, the global community of nations agreed to a set of principles, codified in the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention, that people facing persecution for reasons such as race, religion, nationality and political belief could apply for asylum in other countries. The US became a signatory to the Convention, and Congress ratified those protocols into law. Thus individuals who seek asylum are exercising a right under US law. For this reason, most asylum seekers do not cross the border illegally. Those who come to the southern border typically present themselves to a Border Patrol officer to formally initiate this process, which begins with a credible fear screening and ends in an asylum hearing before an immigration judge.

Applying for asylum is not, of course, a guarantee of asylum. It is a system put in place to screen and adjudicate who qualifies and who does not. Those who do not face persecution, and come to the US for other reasons such as work – economic migrants – will be turned away, either by an interviewer at the border or by a judge in court. Those who advocate restricting the asylum system argue that many know they do not qualify, and present themselves at the border anyway in order to get a hearing in the US, only to disappear: a scenario they describe as “catch and release.” But nearly all asylum seekers – over 90 percent – show up for their day in court, because disappearing would mean a living permanently as undocumented, and giving up the possibility of legal residency. And if some asylum seekers are not facing persecution, or are lying, determining this is the very purpose of the immigration court system.

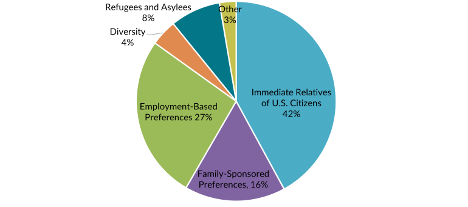

Myth: Most new immigrants are asylees and refugees

For all the public debate about asylum seekers and refugees – a separate category which encompasses those granted asylum before they reach the country where they are to be resettled – it is disproportionate to their makeup of new immigrants. Of all the new immigrants to the US, a relatively small number of them are asylees: just 8%. By far, the largest share of new immigrants – more than half – are those with relatives in the US who can sponsor them to come. This is because the US immigration system favors family unification, under the presumption that families provide more stability and support to new migrants and prevent them from becoming “public charges,” dependent on welfare.

The next greatest share is those who are brought over for a job. Employers can also sponsor people to come to the US to work, particularly if they have particular skills, or are in particular industries which run on a mostly immigrant workforce. There is great demand from employers to have access to such a workforce; thus there is strong political support to maintain this from the business sector.

In comparison, asylum seekers and refugees are a tiny percentage of people who come to the US every year. Yet they are often portrayed as a massive human wave, overwhelming our borders. This perception has more to do with the backlog of cases in immigration courts and the lack of resources to process new asylum claims in a smooth fashion, or allow them to work to support themselves in a timely fashion. This is a problem that has more to do with funding and hiring decisions within the US government, which produces a chaotic process at the border which makes the news.

Source: Migration Policy Institute tabulation of data from Department of Homeland Security (DHS), “Table 10D: Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Broad Class of Admission and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2022,” updated August 21, 2023, available online.

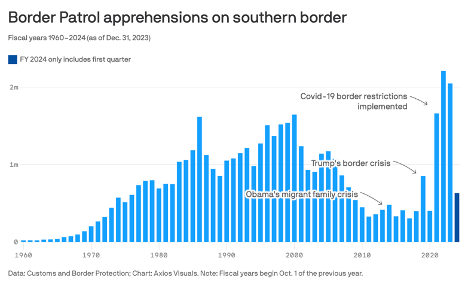

Myth: The border crisis is unprecedented

We measure border migration by apprehensions by Border Patrol. In recent years, this number spiked to a record high in 2022, before going down again. Yet if we take a longer view, we see that border numbers were relatively low for most of the 2000s – far lower, in fact than the last peak, a much longer and sustained period of high migration which lasted roughly from 1986 to 2001 – dropping after the post-9/11 lockdown.

Source: Contreras, Russell and Stef W. Kight. “3 Presidents, 3 Border Crises.” Axios Feb. 11, 2024

Even this measure is misleading, because we measure border numbers by encounter, not by individuals. And when the government takes more aggressive measures to curb border crossings, these can actually increase border encounters, because individuals who are caught and turned away are coming back and trying to cross again, and counted multiple times. Under the Trump and Biden administration’s Title 42 restrictions, coyotes were known to be pricing three or more crossing attempts into their fees. Ironically, harsh immigration enforcement measures ended up spurring more border crossings, thus artificially inflated the appearance of the border crisis which justified those very measures.

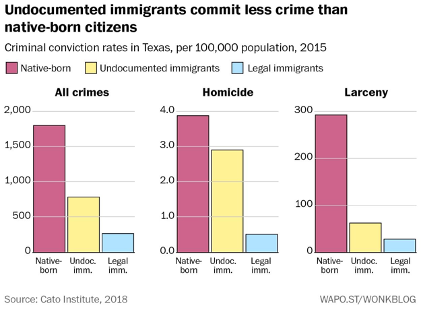

Myth: Crime and migration are correlated

Much fear of new migration is driven by fear of crime, and the presumption that large numbers of new migrants make Americans unsafe. Nativist politicians make reference to organized crime groups made up of immigrants to suggest that immigrants are disproportionately criminals. These popular fears change with the times: in the 19th century, new Chinese migration spurred tabloid stories of “white slavery” by Chinese triads; in the 20th, books and movies about Irish gangsters and the Italian mafia accompanied migration from those two countries; in the 21st, shows about sleeper cells of Muslim migrants accompanied refugees fleeing the Iraq and Afghanistan wars; today, movies and shows about narco cartels are popular, reflecting migration from Latin America.

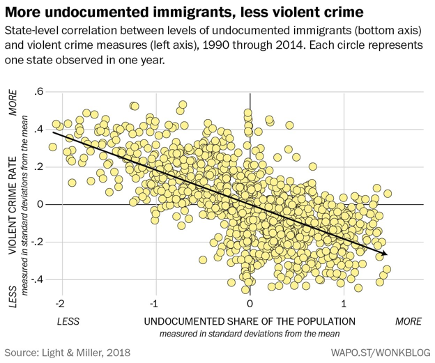

Yet these salacious stories, however entertaining, never bother to consult academic researchers. If they did, they would know that an entire body of scholarship finds no connection between immigration and crime. This holds at both individual and geographic levels. That is, statistically, immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than non immigrants, and areas that have a greater percentage of immigrants have less crime than areas with a greater percentage of native-born Americans. This holds for undocumented immigrants – those most commonly assumed to be criminals – and for violent crimes.

Source: Nowrasteh, Alex. “Criminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Comviction and Arrest Rates for Homicide, Sex Crimes, Larceny, and Other Crimes. Cato Immigration Research and Policy Brief No. 4, Jan 26. 2018.

Source: Light, Michael T. and Ty Miller. “Does Undocumented Immigration Increase Violent Crime?” Criminology March 25, 2018.

Political scientists, criminologists, and demographers have looked at this question and all reached similar conclusions: that when it comes to the question of do immigrants commit more crime, the answer is no. Politicians can cherry pick anecdotes of crimes committed by immigrants to highlight in their speeches. But they could also look for, and find, crimes committed by dentists, Methodists, or grandparents. Anecdotes alone do not prove that those populations commit crimes more than non-dentists, non-Methodists, or non-grandparents.

Myth: Undocumented immigrants live off of welfare

One of the fears often expressed by politicians is that a greater number of undocumented immigrants in the US will bankrupt social welfare and entitlement programs, specifically Social Security and Medicare. In reality, noncitizens – including undocumented immigrants – cannot receive Social Security, Medicare, or most forms of social assistance such as Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), exchanges under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as food stamps).

In fact, undocumented immigrants are net contributors to entitlement programs because they pay taxes to support programs which they are ineligible to receive. When anyone gets a formal job, they are required to provide a Social Security Number to have their payroll taxes deducted from their paychecks, which will then fund Social Security and Medicare. When undocumented immigrants are hired, they make up a number. This means that those same payroll taxes are deducted, but those funds go toward benefits which they will never collect.

At the local level, there are public expenses which go up with new residents, including undocumented immigrants. These include costs borne by school districts, if their children enroll in public schools. And a limited number of state welfare programs, principally Women, Infants and Children (WIC), can be accessed by anyone regardless of immigration status. Certain municipalities that have seen an influx of new immigrants, notably New York City, have experienced a sharp rise in public costs associated with temporary housing due to New York’s unique right to shelter. These costs are partly offset by sales tax revenue from goods and services which immigrants pay for. In total, undocumented immigrants pay $96.7 billion in taxes each year, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

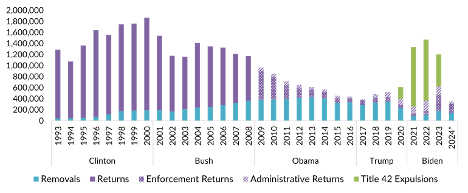

Myth: Republicans deport more people than Democrats

There has long been enthusiasm for deportations by Democrats and Republicans alike. Former president Donald Trump has campaigned on promises of mass deportations. But he sent back fewer people than either Joe Biden or Barack Obama. Obama served two terms compared to Trump’s one. But In those two terms, Obama – whom immigrant rights advocates called the “Deporter in Chief” – removed or returned over 5 million people. Even Obama’s record does not compare to his predecessors, George W. Bush, or Bill Clinton, who sent back over 10 million and 12 million, respectively. And no president was more consequential than Clinton, who in 1996 signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which lowered the standards for removal and inaugurated the current era of mass deportations.

What we commonly call deportations consists of several categories: administrative returns, enforcement returns, removals, and expulsions, which different presidents have relied on to different degrees. The difference is that Democrats have tended to prioritize returns at the border – sending migrants away immediately without a formal removal order – while Republicans prioritize interior removals: sending immigration enforcement agents to arrest those already living in the US without authorization. But in total, in the last several decades, Democratic presidents have sent back more would-be migrants than Republican presidents.

Source: Chishti, Muzzafar and Kathleen Bush-Joseph. “The Biden Administration Is on Pace to Match Trump Deportations Numbers – Focusing on the Border, Not the U.S. Interior.” Migration Policy Institute June 27, 2024.

Myth: Immigration has always been a divisive partisan issue

For much of US history, immigration was largely an administrative and diplomatic question. Anti-immigration attitudes existed since the founding, and nativist movements – from the Know-Nothings to the Ku Klux Klan – have at different moments targeted new Americans from Germany, Ireland, Italy, China, Latin America, and the Middle East. However immigration policy was not a top issue on which politicians ran for most of US history. Before the Civil War, immigration restrictions were set at the state, not national level. Slaveholding states resisted efforts by the federal government to enforce immigration laws at all, fearing that a government that could regulate the movement of people could also regulate the buying and selling of people.

Birthright citizenship, which was already largely recognized by common law, was codified by the 14th Amendment, which was ratified not with immigrants but formerly enslaved people in mind. It was only the “crisis” of nonwhite immigration that first made immigration a national issue: an influx of Chinese laborers brought to the US to build the railroads, who were later barred under 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act – the only time a specific nationality was barred from the country by US law.

Even then, immigration and refugee laws were considered treaties between sovereign countries, negotiated by diplomats rather than by Congress. It was not until the 1920s that comprehensive national immigration laws were ratified, with the Quota Law and Johnson Reed Act. These laws set limits by nationality aimed at keeping out Southern Europeans, “proven” by the pseudoscience of eugenics to be racially inferior to Northern Europeans. These quotas proved politically unsustainable and were done away with after World War II, amid embarrassment that US immigration law was based on the same race science favored by the Nazis.

The law which replaced it and became the basis for today’s immigration rules, 1965’s Immigration and Nationality Act, was also sold as a restrictionist measure, because it replaced quotas with family sponsorship, under the assumption that few nonwhite immigrants would be sponsored because most new Americans at the time were European, owing to the past national quotas.

Since then, there have been various efforts at immigration reform, and prior to the current era, they attracted support – and opposition – from Democrats and Republicans alike. Before the present, the highest border numbers in the modern era occurred under the Reagan and Clinton administrations. It is only relatively recently that immigration became a top political issue, a central plank of party policy platforms, and subject of sharp partisan debate. It was not changes in immigration levels or in immigration law which precipitated this shift. Rather, it was changes in the parties themselves, which for over a century were divided on the issue, and in recent decades, consolidated their constituencies as more uniformly dovish or hawkish on immigration.